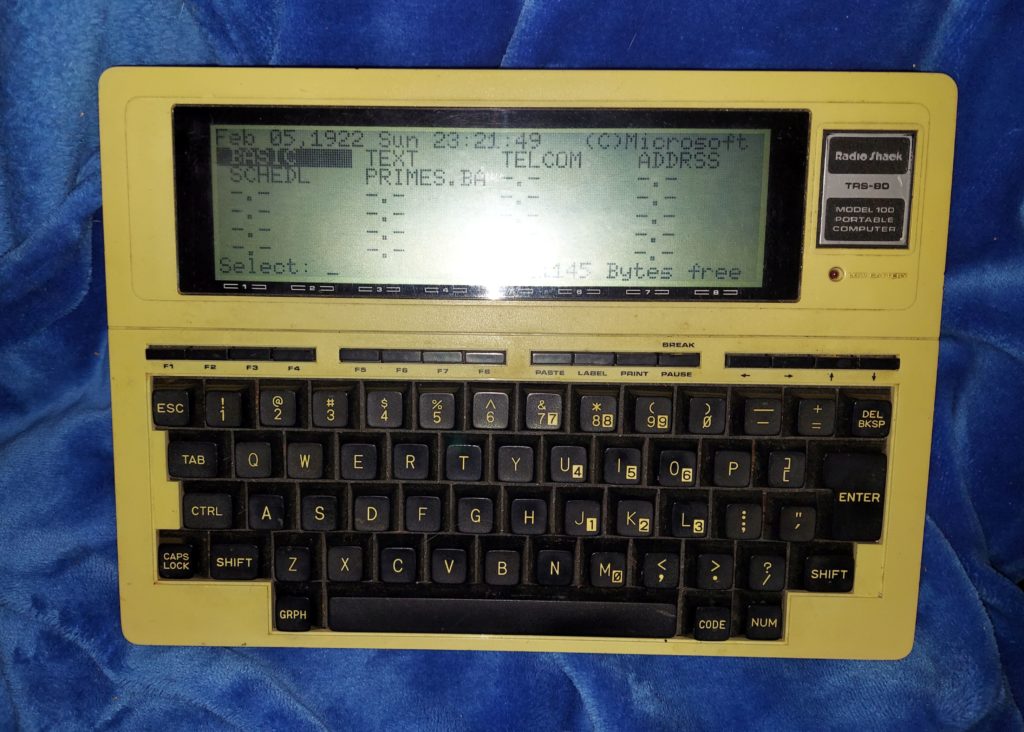

(I’d update its date to 2023, but it wouldn’t believe me.)

The TRS-80 Model 100 was one of the first popular “laptop” style computers. Offered for sale in 1983, it was a revolutionary device. Users could choose from built-in BASIC as well as rudimentary word processor, scheduler, address book, and terminal apps. It spoke a surprisingly mainstream dialect of BASIC for the day — a lot like IBM BASICA available on the first DOS machines.

Power was provided from either a wall-wart adapter or car adapter, or four AA batteries, which would actually run the machine for many hours. (Radio Shack claimed about 20 hours runtime, and I found that believable.) A memory backup battery was also provided, so if the AA batteries ran out or were removed, you didn’t lose your data.

Program storage was either the 22KB of battery-backed-up memory, shared between program storage and RAM, or “bulk storage” via audio transfer to cassette tape. There was an obscure “Disk/Video Adapter” (the size of a small PC) that could connect to the Model 100 via the expansion port on the bottom, and allowed it to read and write low-density 5.25″ diskettes. It was more reliable than the tape option — but then again, so was almost literally anything else.

There was a built-in direct-connect modem, and with the addition of a phone adapter cable, the Model 100 could dial in to a server. Dial up BBSes (Bulletin Board Systems) were the “Internet” of the day; most of the menus were designed for full-size CRT terminals and didn’t look good on the Model 100’s small LCD screen — but the “killer app” for these was the ability for journalists to call in and directly upload draft articles straight from on-assignment locations, using only a phone line. (The alternative tech was to use a fax machine and have someone re-type the article.)

One thing that the Model 100 was great at was RS232 serial communication. Back in the day when 9,600 baud was the standard that all the cool, high-speed kids used, the ability to do serial comms at any speed from 75 baud to 19,200 baud was amazing. And the Model 100 could do this with 6, 7, or 8 data bits, one or two stop bits, with parity bit options of Mark, Space, Even, Odd, or None. (That’s literally every option mathematically possible, for those keeping score.) If it had a serial port, the M100 could talk to it.

One serial device that I got it to talk to was an old LORAN-C receiver that I picked up for cheap at a hamfest. LORAN-C was a wide-area navigation system from back before GPS and friends were available to non-military users. LORAN (short for LOng-RAnge Navigation) used time/phase differences in groundwave signals sent from sites around the US to determine the user’s position. Finding the time difference between two sites resulted in a hyperbolic line of location. With two (or ideally more) pairs of stations, the position could be determined by the intersection of these positions.

The Model 100’s BASIC turned out to be fast enough to listen to the data provided at NEMA 4800 baud from the LORAN, compress it using a keyframe-plus-deltas scheme I came up with, and store it in its memory. 22KB of memory — not enough for a modern app’s icon — was enough to record some eight hours of position data, with a latitude/longitude fix every six seconds (which was all the LORAN would do.)

I used it to track position data on trips between home (northern VA) and college (Norfolk). On a whim, I did a complete cloverleaf interchange tour on one trip home — taking each of the four 270-degree ramps and continuing on in the original direction. When I got to school and downloaded and plotted the data, the cloverleaf was visible, if somewhat distorted (even driving slowly, a car moves quite some distance in six seconds.)

The 1980s may not have had VR, ChatGPT, or even the Internet as we know it — but we did a lot with almost nothing.